A Few Thoughts about the Hasan Minhaj Story

And some cold hard numbers.

Everyone is clamoring to know what I think of the Hasan Minhaj story. Whenever I leave the house to tend to my various errands and engagements, I inevitably run into someone who asks: “Seth, do you think what Hasan Minhaj did was bad, and if so what are the proper consequences?” My phone is abuzz with texts and calls and direct messages, my mailbox overflows with letters. “Is it so terrible to make things up?” they want to know. “Where is the line? Does he of all people deserve this level of scrutiny? Aren’t there worse villains by many orders of magnitude? What of comedy’s rapists and transphobes, the propagandists and neo-Nazis? Why won’t the New Yorker give Joe Rogan this treatment, or Tim Dillon or Louis CK? I have so little time to care about anything in this world, and yet there is so very much to care about. Why Hasan Minhaj?”

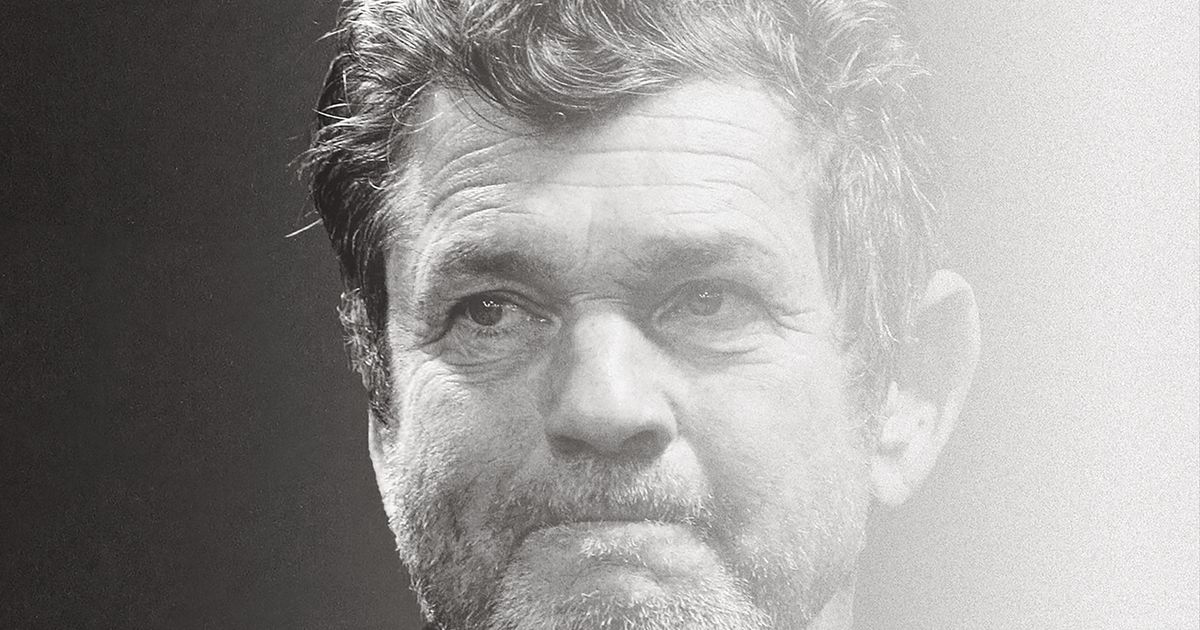

Okay, fine! There are a few interesting things to take away from the New Yorker’s exposé on Hasan Minhaj’s fabrications, most of which you’ll find in other pieces, specifically Nitish Pahwa’s in Slate and Ryu Spaeth’s in New York. For my part, I do think the story merits this level of attention, largely because I think almost all famous comedians deserve this level of attention. Comedy is important, and the relative dearth of serious reporting on the art form—let alone traditional literary criticism—has allowed a vast army of grifters, hate-mongers, and straight-up robber barons to infiltrate it. More germane is the fact that Minhaj is a serious candidate for one of the industry's most powerful positions, one that would 1) give him a massive international platform and 2) put him in charge of an influential workplace. Whether he has abused his audience’s trust and whether he’s a good boss are questions of clear public interest. Best to get any skeletons out of the closet before he gets the job.

What has been most striking to me in the last week is how practically nobody in comedy has defended Minhaj. This is… rare, I think! In recent years we’ve seen comedians go to bat for their friends over conduct much worse than his. The industry has a frighteningly powerful thin-blue-line mentality, even in its more liberal cohorts. That the wagons are not circling around Minhaj is certainly reflective of the left’s willingness to police its own more vigorously than the right, but I wonder if it might also suggest that despite his success, for whatever reason, he has few friends in the industry. I don’t mean to sound conspiratorial or to imply that he is some whisper-network monster: perhaps he’s just bad to work with and not very funny to boot. It’s just… how do I say this… very weird to see a consensus form around the correct moral position in a subculture where this basically never happens? And somehow I don’t think we can soundly attribute it to an industrywide reverence for truth or a distaste for the use of comedy to execute personal grievances. The man just doesn't seem to have much of a constituency, which perhaps speaks to the decline of his brand of info-comedy.

Anyway, excellent article. Nicely done. And F phonies and hucksters of all stripes.

— Miles Kahn (@mileskahn) September 15, 2023

The absence of any spirited defense brigade is interesting to me because it illuminates the role those brigades played in other (again: MUCH WORSE) cases. I have argued before that friendship is an essential survival mechanism in the face of Alleged Comedian Misconduct, be it abuse or bigotry or serial disregard for the contract between performer and audience. People like Louis CK and Chris D’Elia and Jeff Ross and Joe Rogan and Dave Chappelle have evaded lasting professional consequences for their behavior in part thanks to the support of gatekeepers (venue owners, agents, managers) and platform owners (Google, Spotify, Netflix), but also because their friends stood by them, in turn communicating to fans and gatekeepers alike that their behavior was acceptable. Chappelle’s continued popularity is directly attributable to the comics—like Jon Stewart and Michelle Wolf—who kept working with him in the wake of his transphobic rants. Louis CK’s story would be very different if other comics shunned the Comedy Cellar after it welcomed him back; ditto Jeff Ross at the Comedy Store and D’Elia at the Laugh Factory or the Improv. We cannot underestimate the power of social censure, especially after striking WGA and SAG members successfully leveraged it to dissuade Drew Barrymore and Bill Maher from crossing the picket line. Friendship, by which I really mean labor solidarity, can empower bad actors as surely as it can be wielded against them. The money isn’t nearly as important to these people as the social club.

Of course, it remains to be seen what the New Yorker story will mean for Hasan Minhaj. My prediction is that he won’t get the Daily Show job—too many liabilities, not enough allies—but his standup and acting careers will continue unaffected. He still has fans, and at the end of the day his conduct hardly rises to deplatformable levels. Here, though, is where I am equipped to give you something you won’t find anywhere else: an idea of how much his “emotional truths” are worth in the market for standup comedy. As you know, I have a little side project gathering publicly owned universities’ contracts with comedians. Sometimes these are for shows produced by student groups and paid for with university funds, usually for a flat fee. In other cases, the comedian is renting out a university-owned venue and taking a cut of the receipts, as is typical for comedy shows you see in a theater or stadium. My anecdotal sense is that most college shows tend towards the first category—student groups paying a flat fee not tied to attendance—which means these contracts only offer a limited perspective into a given comedian’s earning power. But a limited perspective is still a perspective.

Okay, enough preamble. I’ve obtained info for four Hasan Minhaj events: one at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, in 2018; two at the University of Maryland College Park, in 2017 and 2020 (the latter being a virtual Q+A); and one at Indiana University Bloomington in 2021. All occurred after Netflix released his first special, Homecoming King, and all but the first UMD show were after the premiere of Patriot Act. And here are the fees. UI paid $45,000; UMD paid a total of $70,650 for two half-hour Homecoming shows in 2017 and $60,000 for the virtual chat in 2020; and IU paid $130,000 for the 2021 event, a keynote address and moderated discussion co-sponsored by the Society for Professional Journalists.

We could get into how Minhaj’s rates compare to other comedians, but again the dataset is so limited that I don’t know if it would actually be a meaningful comparison. The point is that he’s in the calibre of entertainers who can earn a median household income in an hour or two of work, and the New Yorker story isn’t likely to change that. The other point is that his grift—and I think it’s fair to call it a grift—was very lucrative.

This gets back to why I think there should be more of this sort of journalism, even if it might seem weird or distasteful to fact-check a comedian’s stories. These people really do make quite a lot of money, money that both reflects and burnishes their legitimate cultural influence. Their fans can treat them with as much adulation as they like, but I don’t know why journalists should approach popular social commentators with anything but skepticism; in fact, I think skepticism is an imperative when dealing with people whose product is themselves. You never know where a few simple questions might take you.

One last thing. Consider that Indiana University event in 2021, a speech and Q+A for which IU and the SPJ paid Minhaj $130,000. Here’s what he used that speech to say, per IU’s student newspaper:

In his performance, Minhaj summed up why stand-up comedy allows him to communicate authentically.

“Comedy is about honesty,” Minhaj said.

And here’s what his audience made of it:

As Minhaj relayed the experience of growing up being a South Asian American as a critical component of his identity, [Q+A moderator] Bokil said he believes Minhaj’s genuine recount of his experiences are what make him relatable to everyone, regardless of ethnic identity.

“He’s someone that is relatable,” Bokil said. “You could sense that with the audience with the laughter that he brought and the audience clapping, making it entertaining and informative at the same time.”

Hasan’s authentic and laid-back approach made his talk entertaining to IU students, master’s student Srinagh Chalasani said.

“It was interesting because he was sharing his life experiences and mixing it up with humor,” Chalasani said.

Audiences are powerful things. I see little reason to be generous towards anyone who makes piles of money building them.

What Else?

I had several other things I wanted to get into today, but then I just wrote like a thousand more words than I planned to about Hasan Minhaj. So, real quick:

-More on it later, but I highly recommend Django Gold’s special Bag of Tricks, which for me hit the same sweet spot as Anthony Jeselnik and Tim Gilbert:

-I saw the new Annie Baker play Infinite Life yesterday, which I enjoyed very much and which reminded me of this 2010 Brooklyn Rail conversation between her and GLOW co-creator Carly Mensch, which gets into some interesting thoughts about humor and laughter. (Including a cameo by the phrase “emotional truth.”) I don’t think I’ve mentioned it before, but APOLOGIES if I have:

Baker: So just quickly touching back on the subject of comedy and laughter before we move on: when I was in school I wrote a long super-pretentious paper on laughter and comedy! The paper was on Beckett’s Watt and why I thought it was a) the funniest novel of all time and b) also a kind of treatise on laughter itself. At one point in Watt a character says:

"The bitter laugh laughs at that which is not good, it is the ethical laugh. The hollow laugh laughs at that which is not true, it is the intellectual laugh.But the mirthless laugh is the dianoetic laugh, down the snout—Haw!—so. It is the laugh of laughs, the risus purus, the laugh laughing at the laugh, the beholding, the saluting of the highest joke, in a word the laugh that laughs—silence please—at that which is unhappy."

Anyway, I just went crazy over this quote. I won’t get into all the reasons, but somehow this “laugh laughing at the laugh” described to me what exactly I think is so great about Beckett. I also became obsessed with this idea of the “highest joke,” which for me was the gap between reality and language, or the simultaneous lack thereof. Like the more you try to convey reality through language, the more it becomes clear that there is a reality that language cannot express. But at the same time, language is the only reality we know. And that to me is just this amazingly sweet and comic paradox. And then I realized that pretty much all my favorite comic plays and novels deal in some way with this paradox. The laughter produced by these works is not so much directed towards the characters as directed towards language itself, and its gorgeous artificiality and insufficiency. Most comedies these days just involve ethical and intellectual laughter, and I always find them unsatisfying. I can’t say that I’ve ever achieved the risus purus in my own work, but I am sort of always striving for it in my unhappy little way.

-From The Guardian, a look at sexual abuse in the Australian comedy scene:

That the workplace of “comedy” is so nebulous doesn’t help. The industry is populated by freelance performers who rely on a constellation of bookers, festivals and venues. Those who spoke to the Guardian said standup in particular had its own set of risks: the male-dominated scene tends to reward outsized egos and strong personalities or stage personas; emerging comics can find themselves thrown together with the famous, creating a vulnerable power imbalance; the gigs happen at night in venues fuelled by alcohol; and you’re often there alone.

“You’re on stage alone, you’re touring alone, you get thrown in with other people randomly,” Fricker says – which can be harder for women, queer people and for people of colour.

“In comedy you’re meant to be seen as laid-back and kind of silly, and there’s a lot of encouraged drunkenness,” Lardner says. “If you’re not palling about, you genuinely will get less gigs.”

-I enjoyed Fran Hoepfner’s thoughts on Brian Jordan Alvarez.