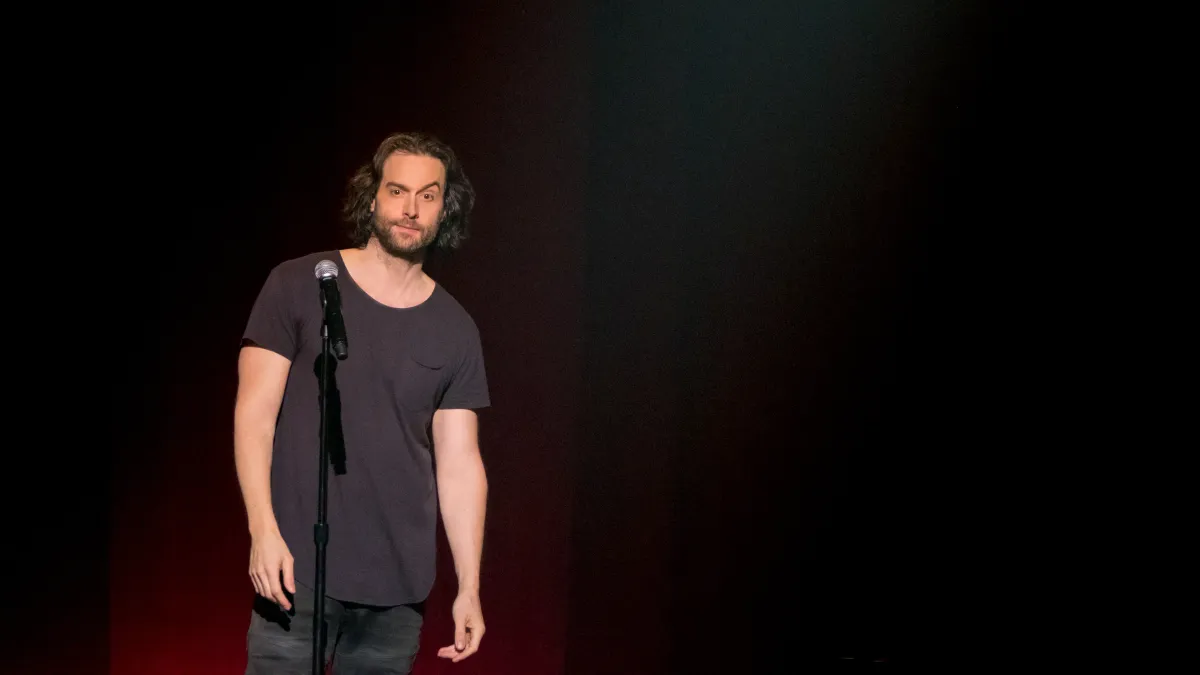

Chris D'Elia's Back

Does anyone give a shit?

Hello: thank you for reading Humorism. If you can, please help keep this newsletter going by updating your subscription for six bucks a month:

Chris D’Elia’s back. I’m not sure what to say that I haven’t said here a million times already. But I don’t see anyone else saying it, and it needs to be said, so: Chris D’Elia’s back. Last weekend he headlined at Levity Live in Oxnard, California, part of the Improv chain of comedy clubs. The lineup included alleged rapist Bryan Callen, cycling enthusiast Brendan Schaub, and D’Elia’s longtime opener Michael Lenoci. This weekend he performed at the Hollywood Laugh Factory, owned by Jamie Masada, in lineups that included Schaub, Maz Jobrani and Theo Von. Next weekend he’s booked at the Laugh Factory’s San Diego location. He appeared on Von and Schaub’s podcast twice this month, joined in one episode by comedian Erik Griffin. He’s back. This is how it starts.

For those just joining in: back in June 2020 D’Elia was accused, by a staggering number of people, of aggressively pursuing young and underage girls on social media. Two fans told the Los Angeles Times he exposed himself to them in a hotel room. Another said that when she was 19 years and he was 37, he told her “he would meet up with her only after she performed oral sex on one of his friends.” One woman said he cold-messaged her on Instagram when he was 36 and she was 17. “It was clear I was in high school,” she told the Times. “I had 16th birthday pictures and photos of me at football games.”

A few months later, CNN reported on allegations that he exposed himself to three women without their consent. Two comedians who knew him well told CNN he had a reputation for that. "There's a lot of people who will say when the MeToo stuff happened, we were all thinking, 'What about D’Elia?’” one of them said. “He just seemed really profligate with the way he would go after women, sleep with women, expose himself to women.”

At the time, D’Elia said all his relationships were legal and consensual, insisted he never "knowingly" pursued underage girls, and apologized for getting “caught up in my lifestyle.” His reps dropped him, Netflix axed a prank show it was developing with him and Callen, Spotify removed four Joe Rogan Experience episodes he appeared on, and Zack Snyder replaced him with Tig Notaro in Army of the Dead. (One person stood by him: Hollywood attorney Andrew Brettler, who represents or has represented Prince Andrew, Horatio Sanz, Armie Hammer, Bill Cosby, Chris Noth, Brett Rattner, Ryan Adams, and Chris Brown.) He took a time-out from public life and returned to his podcast eight months later, telling fans he was “on this path of recovery.” He amassed one million TikTok followers and joined Patreon and Cameo, where he charges 200 bucks for a customized message ($10,000 for corporate customers).

Now he’s headlining at clubs again, with nothing but his own word to show he’s not that guy anymore—the guy who didn’t do what he was accused of anyway. As usual I find myself unable to grasp how an unrepentant creep’s return to the workplace is anything but an emergency. Obviously comedy clubs are even more amoral businesses than talent agencies and film studios—this much I accept. But what about other comedians, all the theoretically good people who work in and around these clubs? Do they want their audiences to be safe? The clubs’ employees? It’s been two years of nonstop sermons about how important comedy is, the joy it brings people, the togetherness, the power it has to change hearts and minds. What good is any of that if it also lets people like Chris D’Elia roam free?

A popular talking point in these discussions—because there are enough dangerous people roaming free in comedy for these discussions to have popular talking points—is that it’s unfair to expect anyone to jeopardize their career by calling out abusers and enablers. I am sympathetic to this argument, but I’ve always found it difficult to get fully on board. For one, I’m not convinced that any one person’s success in comedy is more important than any other person’s safety, let alone the safety of children. Two, I have yet to see any standup comedian take the success they earned through strategic silence and leverage it against the villains they had to keep quiet about. There is apparently no point at which it stops being too risky to do the right thing. Three, the talking point seems to be a rhetorical sleight-of-hand that frames the expectation as “only one or two people take a solitary stand against abuse, please,” rather than “lots of people take a stand against abuse, please.” Comedians are as capable as anyone of joining forces to demand change. They did it at the Comedy Store in 1979. They did it when they wanted higher pay from New York clubs in the early 2000s. They did it when comedy clubs were shut down in 2020. They do it every time Dave Chappelle gets criticized. The wheel has already been invented, and it works quite effectively.

But none of that applies to Chris D’Elia anyway. The guy no longer has powerful representation. There’s no TV network or streaming platform behind him. He sold one of his houses last year. He’s on Cameo and Patreon. (Yes, his father is a veteran writer-producer currently executive producing a Disney series, which is another way of saying he’s someone who really wouldn’t want to add “running interference for my son credibly accused of grooming underage girls” to his resumé.) D’Elia’s only friends right now are 1) the stupidest podcasters in comedy, and 2) club owners, who I hope this newsletter has made clear are some of the most cowardly people to walk the earth. They’ll do whatever it takes to stop comedians from yelling at them. Getting D’Elia out of comedy spaces is an easy layup. If the entire industry weren’t built on the delusion that baseline morality has a self-interest exemption, he’d never have made it back in the first place.

Header image via Netflix.