Congratulations, Colin Jost!

Man gets raise.

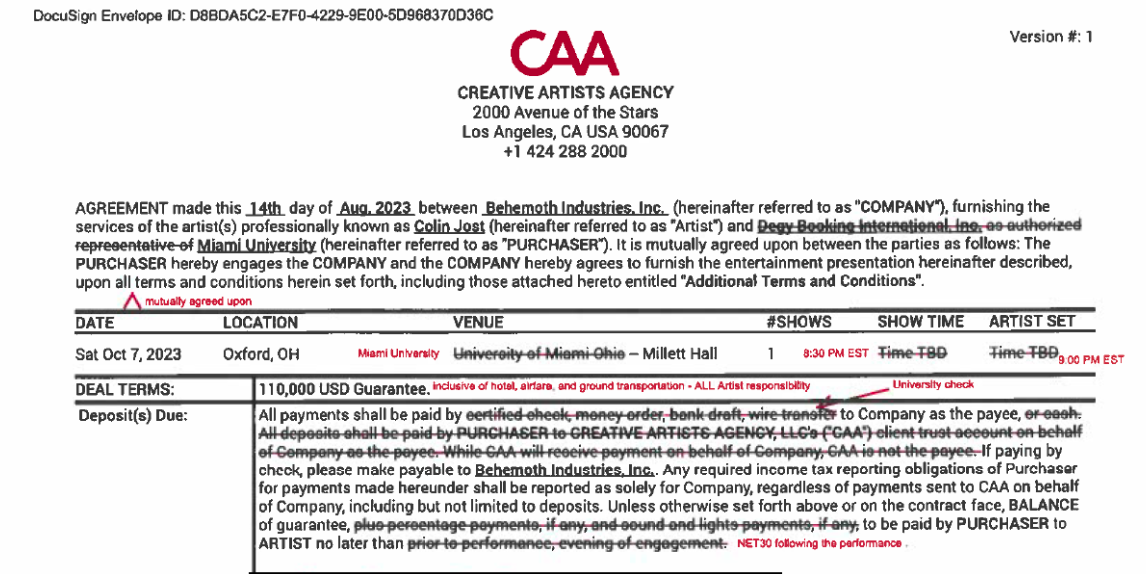

The Humorism newsletter officially commends recurring Humorism subject Colin Jost on his recent successes! As you may recall, in 2021 the former SNL head writer and current Weekend Update anchor commanded a fee of $70,000 for a performance at the University of Illinois. Thanks to his hard work these last three years, Jost, who owns six homes and was recently tapped to host the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, has lately seen his hourly rate increase by more than 50 percent. According to a contract I obtained from Miami University in Ohio, Jost received a fee of $110,000 for a show there in October. See for yourself:

Now, presumably some amount of that fee was shared with his openers, Molly Kearney and Marcello Hernández. (I’d wager they got $5,000 apiece, as was the case with Jost’s support acts in 2021.) Even so, this is quite an impressive sum for a guy who isn’t exactly known for his standup. Here’s what The Miami Student had to say about the show:

At around 9:50 p.m, Colin Jost finally started his set.

There was a lot of anticipation at that point in the night, as his set occurred almost an hour and a half after the event’s original start time. This buildup, combined with the stellar performances from his openers, made Jost’s performance fall a little bit flat.

There were some funny moments — Jost joked about the writer’s strike and a sign that his “Weekend Update” co-host Michael Che wanted him to make that read, “Write Power.” He also told a long, drawn-out story about getting high and buying a rotisserie chicken, 24 Chewy granola bars and two brownies, and described an epiphany he had while rewatching “Beauty and the Beast” that Mrs. Potts is comparable to Ghislaine Maxwell.

However, Jost had more quips that opted for relatability and, consequently, ended up lacking originality or compelling delivery. These included jokes about his first-year dorm experience (where he conveniently left out that he went to Harvard), a Spirit Airlines trash-talk that made it clear he had never been on a budget airline and jokes about his sex life that felt more like bragging about being married to actress Scarlett Johansson.

“My aunt is like, ‘But what if I get canceled?’ I think you’re OK,” Jost said, lamenting how nobody else in the audience had it as rough as he did because they didn’t have to worry about cancel culture.

On the other hand, as we’ve seen lately, $110,000 is more or less in line with what comics of Jost’s stature make from sellout shows at large venues. In fact, it may be on the lower end of things. Per documents I’ve obtained in my research, artists like John Mulaney, Tom Segura, Nate Bargatze, Bert Kreischer, Jo Koy, Matt Rife, and Chris D’Elia all make from north to very north of $100,000 per show. At the much higher end of the things, Dave Chappelle earned $331,237 from a gig in West Virginia in 2022, while Jerry Seinfeld netted a whopping $618,106 from a show in Indiana this past October. I’m somewhat mixing apples and oranges here—those figures are all net ticket sales, while Jost’s was a flat guarantee—but my point is that while his fee may seem shocking, it’s roughly what you'd expect for someone in his position.

Which brings me to my other point. Obviously I’m no fan of Colin Jost. I think he is unfunny, unintelligent, and an all-too-eager cog in a corrupt machine. At the same time, I find him to be a fascinating figure. He’s the platonic ideal of an establishment hack, someone whose combination of luck, credulity, and ability to play the game effectively guarantees a life of fame and wealth. Other than Lorne Michaels, I think he may also be the closest thing to a personification of everything wrong with SNL: namely, its dual function as kingmaker and vampire, awarding lifetime sinecures based less on talent or originality than on one’s dedication to making mediocre work. In an interview published yesterday in Salon, I went long on my belief that SNL is bad for comedy. Jost makes the case much more concisely.

I’ve argued all this before, but I’ll take any opportunity to repeat it: there is a large class of comedians who effectively have the power to turn on a gigantic money spigot whenever they please. Curiously, their entire industry is collapsing around them. Club pay has stagnated for decades; clubs themselves are run by unaccountable, incompetent, and usually right-wing maniacs; mainstream gatekeepers have abdicated their duty to take risks on untested artists; and pretty much all that remains of the talent pipeline is the vague hope that if you produce work at your own expense for long enough, Netflix (or SNL) might eventually take an interest.

This is an extremely bad state of affairs. Short of massive federal arts funding, I see only one obvious remedy. As I wrote a few years ago:

To put things differently: comedy’s biggest stars and many of its smaller stars earn more in one tour than many comedy venues earn in a year. Remember, the data I’ve collected only shows what comedians make from public universities: for most of them, ordinary private venues (not to mention private universities) likely comprise a much bigger piece of the pie. The two 2017 dates for which Adam Devine earned $100,000, for example, were part of a 26-stop tour.

Now, I know it’s not news that there are lots of rich people in Hollywood. What I hope to impart here is how easy it would be for enterprising venues to decouple pay from revenue, if not to decouple revenue from sales entirely. The mid-to-upper echelons of the industry are full of comedians who owe their careers to local comedy communities they could give tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars without batting an eye. (So could talent agencies, for that matter.) Their donations would handily serve their own interests, both by cultivating future collaborators and by ensuring the sustainability of venues where they perform. More importantly, this system could help shift the political economy of comedy away from self-interest altogether and toward something more mutualistic than it's ever known. Imagine a world where comedy workers are not dependent on the goodwill of tyrannical small business owners to survive; imagine a world where they’re dependent on each other. I daresay it’s possible.

I hate to say it, but comedians may well be the solution to comedy’s problems. I wonder what it will take for them to step up.