“I don’t know what to make of it."

When thinkers refuse to think.

There is currently a deadly heat wave in California. If you can, please help out unhoused people in LA by giving to Water Drop. Send me a receipt for a donation of any amount and I’ll extend your subscription to this newsletter by one month. (This goes for a donation to any cause, but, Water Drop is the one I’ve chosen to plug here today.)

I find it very interesting when standup comedians, who are professional thinkers, find themselves unable to do their job, which is to come up with opinions about things. I will give you an example. On Thursday the comedian Neal Brennan released an episode of his podcast in which he and co-host Bianca Sia discussed Jeff Ross. He has since deleted the segment from the audio and video versions of the podcast, but not before I transcribed sections of it and took notes on the rest. First a recap, then some discussion.

“Our friend Jeff Ross got popped,” Brennan starts. “They said he dated a 15 year old when he was 33.” Sia says they already talked about the allegations last month, and Brennan responds that now they’ve been reported by Vulture. This makes the story more serious, he says, because now lawyers are involved.

“It seems bad. It’s one woman that he dated,” Brennan says. “I don’t know what to make of it… I don’t know what to make of it. I know that I just got offered 15 more minutes a night at the Store.” Of course he’s not going to give up his own stage time because of Ross, Sia riffs. “I don’t know what to do,” Brennan repeats. “I don’t know what to make of it.”

“How do you prove it? And what should the punishment be?” he asks. “Let’s say he did it… some kind of sex. They dated and you assume, if you’ve dated before, one of the best parts of dating is the sex part. So I guess I’m curious about, what do I do? What does Bianca do? What does showbiz do? What does the Comedy Store do?”

Brennan and Sia remark several times that the story hasn’t “caught steam,” which they seem to think makes it less actionable. “It didn’t get the heat that D’Elia got and it didn’t get the Louie heat,” Brennan says. Sia notes that Ross “addressed it and now it’s a bit of a he-said-she-said. That’s where you jam the system, ‘cause, like, D’Elia waited too long [to respond] and what he put out was sort of incriminating.” She asks, “Do you hire him? Would you hire him?”

“The problem with all these things is the amount of blowback,” Brennan answers. “The question becomes, is he worth the trouble? If one person complains… Like, he does corporates. He does a lot of corporates. I would assume that’ll dry up. But it’s not… The story didn’t catch fire. There's also, I think, something to be said for 'he dated her.' So doesn't that… that seems more legitimizing or that seems more dignified.”

“Yeah,” Sia responds. “It wasn’t this sordid, late night, forced-in-a-green-room situation.” She says that “even if it was underage,” in many states it’s legal to marry people under the age of consent. They start googling marriage laws, and Brennan observes that “at least 200,000 minors” were legally married in the US from 2000 until 2015. “Maybe that’s the problem with Jeff, is he didn’t marry her,” Brennan says. “He didn’t make an honest girl out of her… I wouldn’t even say woman ‘cause she wasn’t a woman, she was a child. He didn’t make an honest child bride.”

“People bring up Seinfeld dating Shoshana,” Brennan says, which he didn’t think was gross. “She was 17!” Sia says. “That’s legal in New York,” Brennan replies, adding that Seinfeld once “did a joke that told me nobody was being taken advantage of there.” Then he says yet again, “I don’t know what to do… In New York it’s 17, and that’s where Jeff’s relationship was… I don’t fucking know. I don’t know, dude.”

This is a tic I have observed again and again in recent years. Faced with monstrous revelations about powerful men in their industry—coworkers and even friends—some comics magically lose their ability to formulate opinions. After years of spouting any old shit about anything, they suddenly have no idea what to say. Instead they fashion themselves confused, helpless victims of circumstance and defer to the judgment of imaginary external authorities. Here’s Judd Apatow in 2019:

Would he hire a disgraced comic for Crashing? Apatow says he doesn't have an answer for that. "It's complicated, because no one is in charge of anything. There's no one to say, 'You're allowed to work. You're not allowed to work. Now you're forgiven. Now you spoke clearly.' I don't think we're in a different place than any other network head or producer. Every show on the air is deciding who to hire."

The maneuver is to ask for a consensus to form before the comic himself renders judgment. (See: Brennan and Sia harping on the Ross story’s failure to “get heat.”) Often this happens in the same breath that he decries the mob rushing to condemn his peer, who hasn’t been convicted of anything. Another common tactic is to cite the law (burdens of proof, various states’ ages of consent, differing definitions of “assault”) and speculate as to what sentence a court would levy, rather than consider what standards should exist in the comic’s own community, where the comic has power to enforce them. This is a feature especially in conversation about Louis CK: I cannot count the number of times I’ve been asked some form of, “Well, what do you think he did that was so wrong? What should the punishment be for what he maybe did all those many years ago, which no one even accused him of at the time?” It’s all an excuse not to ask the easiest questions in the world: “What do I think? What can I do?”

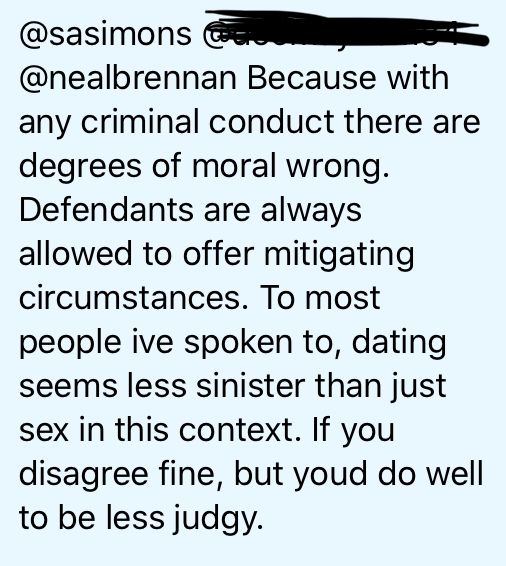

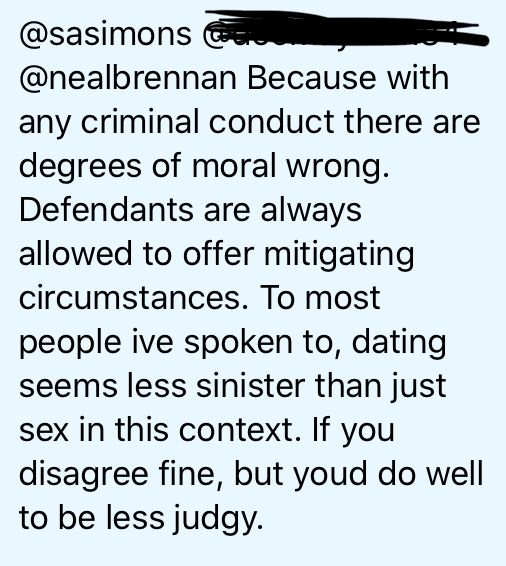

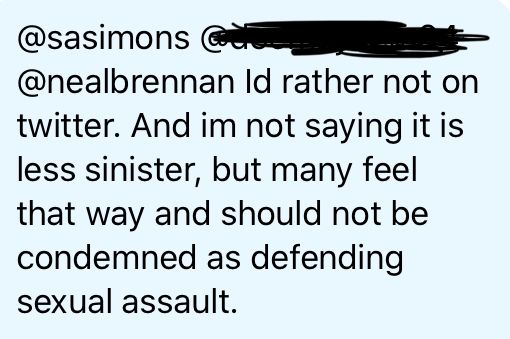

Of course these people have thoughts about the rape allegations against their friends. They have thoughts about everything. That’s their whole job! When professional thinkers create tortured excuses not to think, what they are really saying is that they don’t want to admit their thoughts to themselves or to you. (I kind of can’t believe how quickly Brennan went from “I don’t know what to make of it” to “welllllll, the Store offered me more stage time.”) I’d wager this is because more often than not their thoughts are, I don’t really care and I don’t want to do anything. Yesterday I went back and forth on Twitter with a comic, a regular at the Manhattan clubs. He deleted his tweets shortly after our conversation, and since he’s not a particularly public figure I will respect his wish not to publicly participate in this discussion. But I think it is important to describe one point he made, which was that he’s spoken to many people—comics, I presume—who agree with Brennan. They think Ross’s relationship with Jessica Radtke somehow legitimized his actions.

The Jeff Ross story isn’t just about Jeff Ross anymore. It’s also about his industry’s overwhelming apathy in the face of an almost cartoonishly black-and-white moral narrative. The more I think about it, the more I cannot help but recall the time, not so long ago, a prominent Republican Senate candidate was outed as a pedophile. Several women came forward with allegations that he harassed or assaulted them when they were teenagers and he was in his 30s. Gradually it emerged that his pursuit of relationships with teenage girls was an open secret throughout his political career. In response to these revelations, several of the most cynical, amoral men in the world—GOP elected officials—denounced Roy Moore and called for him to drop out of the race. They of course did not do this out of the goodness of their hearts. They did it because they calculated that he was too toxic. His behavior, now a national story, was an embarrassment to their party, he was doomed to lose his bid for power, and they could gain more from condemning him than from remaining silent. So they did.

Not one powerful man in comedy has made this determination about Jeff Ross. Not even during an extraordinary pandemic, when all the career-making clubs are closed and production is on hiatus, has a single one decided that their proximity to whatever Ross has—friends, money, access, power—is worth sacrificing. In theory now is the ideal time for comedy to look back at the last three years of grisly revelations and collectively figure out how to make the business safer when it returns. In reality it seems powerful men can commit no abuse grisly enough to rattle the old, sexist hierarchies. When live comedy finally comes back, it will be populated by people who could not so much as tweet their disapproval of a famous insult comic’s abuse of a teenage girl. There is no reform, and there is certainly no bottom.