UCB's $200,000 Loan to Ian Roberts

The long debate over the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre's policy of not paying talent reached its most feverish pitch in the winter of 2012 and 2013. A group of standup comics, including Nick Turner and Kurt Metzger, publicly blasted the for-profit theatre over its use of free labor, with Turner going so far as to quit the standup show he hosted. A New York Times article covering the firestorm quoted Matt Besser saying UCB cannot "maintain" its "creative vibe" while paying talent. The theatre held a town hall in which Besser demanded UCB workers push back against criticism of the pay model, setting the defensive tone that would define the conversation for years to come. In an episode of his podcast addressing the debate, Besser and co-founder Ian Roberts reiterated a point the UCB4 have made again and again over the theatre’s history—that they receive no money from it. Here's Besser, per a HuffPost description of the now-paywalled episode:

“[The founding members], in the 15 years the theater has been open, have never taken any money,” he says on Improv4Humans. “So even when the Chelsea theater finally did get into the black [due mostly from paying improv students] ... at that point, we could’ve taken the money the school was making and put it in our own pockets ... all the money we’ve been saving went to opening a theater in Los Angeles.” [Bracketed phrases are HuffPost's, except this one.]

That was not the whole truth. One of the UCB4 had, at that point, taken money from the theatre. According to Los Angeles county records, in 2010 UCB's corporate entities gave Roberts and his wife, Katie, a loan of $200,000. This happened a few weeks after the couple took out two mortgages from Wells Fargo, totaling $936,000, on their new house in Agoura Hills. That house was collateralized in the loan from UCB. Records indicate they paid UCB back by October 2012, three months before the Improv4Humans episode was released.

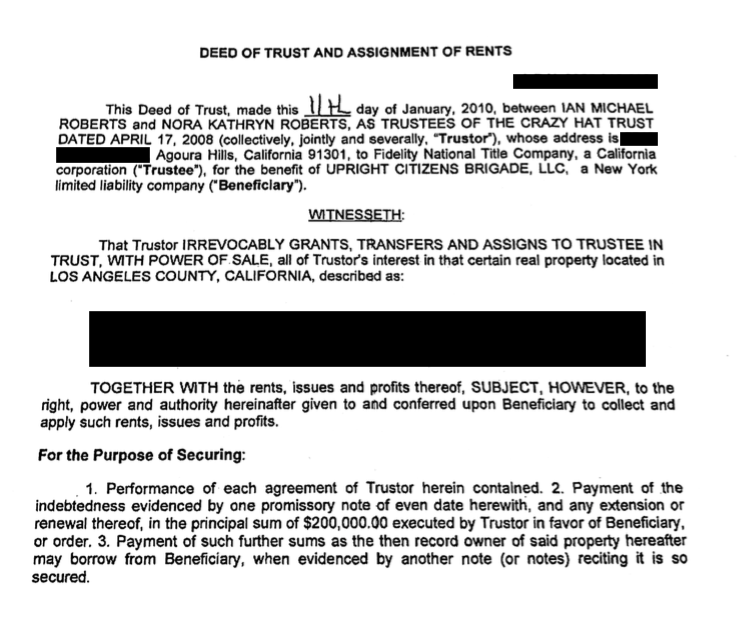

The document recording this loan is a deed of trust, the equivalent in California of a mortgage. Signed in January 2010, the deed lists the Robertses as trustor, or borrower; Fidelity National Title Company as trustee, a neutral intermediary holding the legal title to the property; and Upright Citizens Brigade, LLC as the beneficiary, or lender. The deed pledges the Robertses' home as security for a principal sum of $200,000. It does not mention any interest or maturity date, though this does not mean it had neither: the promissory note specifying its terms is not a matter of public record. Additionally, that the loan was secured by the house does not necessarily mean it was for the house, though this is a sound assumption based on the sequence of loans, and the use of trust deeds for home loans more generally. (UCB did not respond to multiple questions about the loan.)

That was in 2010. UCB was eleven years old. Five years had passed since it opened its first venue in California, four since it opened the training center in New York, one since it began a two-year process of renovating and readying UCB East for a 2011 opening. Classes at the time cost $350 to $375; tickets, $5 to $10. Roberts was executive producing and starring in Players, a Spike TV sitcom created by UCB co-founder Matt Walsh. He was working steadily as an actor and writer, with a recurring role in the final season of Reno 911 a year earlier, and would soon serve as executive producer of Key & Peele. According to transaction records, he and his wife bought the Agoura Hills home for $1,170,000. Today its estimated value is $1,895,400.

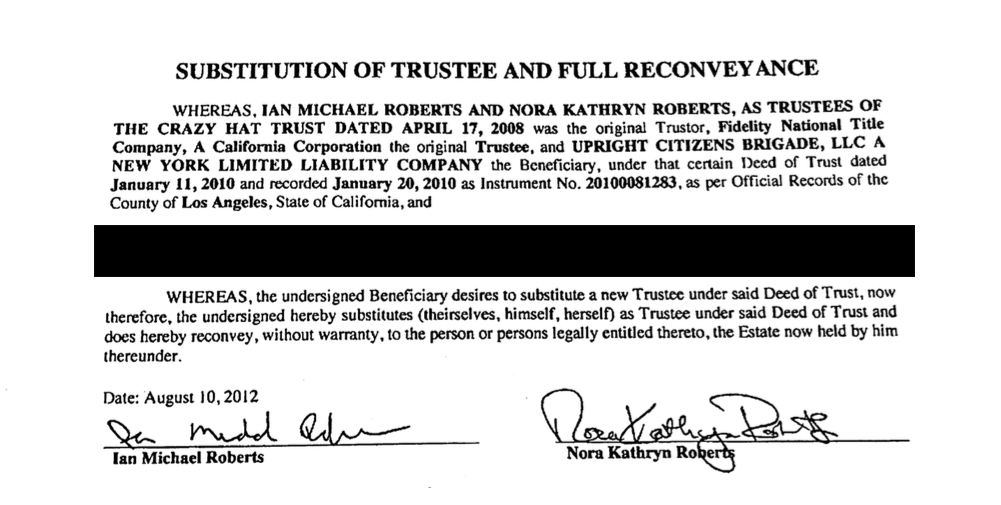

It is important to be clear about what the $200,000 was and was not. It was a perfectly legal loan, and we can reasonably conclude from a 2012 deed of reconveyance that the Robertses paid it back. (There is room for doubt here: a deed of reconveyance releases a debt, but released does not always mean repaid. It just tends to when lenders are not owned and controlled by their borrowers.) The transaction was not, strictly speaking, profit. It was not salary or a distribution or a bonus or a fee for services rendered. UCB did not pay for the Robertses’ house. It simply gave them a loan of $200,000, a sum infinitely greater than anything UCB has ever paid its house talent, and a sum they were able to pay back in two years. It did what any bank does every day.

Is that so bad?

Had Besser said on Improv4Humans that the owners never made a profit from UCB, I do not think it would be fair to call that a lie. But he didn't say they never made a profit. He said they never took any money. The reality is that Roberts took quite a bit of money, money it turns out UCB could stand to part with for two years. In 2010, minimum wage was $8.00/hour in California and $7.25/hour in New York City. Going with the higher figure, $200,000 could have funded 25,000 man-hours of the work UCB’s audiences pay for: not just performance but also rehearsal and sketch writing. UCB could have used that money to pay coaches rather than outsource the cost to talent, as it still does today. It could have covered more than 500 classes for students from underrepresented backgrounds and/or in financial need. It could have paid a regular wage to its sales representatives, who until 2016 worked on commission.

Perhaps UCB could even have done all this and lent Roberts the money. A company with $200,000 to spare is generally a company with more than $200,000 to spare. Remember, this was years before UCB reached its cultural and institutional zenith. Defenders of its business model have long argued that pay would devastate the theatre, that there is simply no money for it, that it would require radical restructuring. Maybe that's true now. Obviously it was not then. Looking back at all that’s happened in recent years—the move from Chelsea in part over an expected rent hike, layoffs, the closure of UCB East over rising rent and property taxes, more layoffs—it is difficult not to wonder what might have been if the UCB4 invested all that money in their workforce rather than in real estate.

At an all-theatre meeting late last year, one UCB worker argued that it was unfair of her peers to ask about the company's finances. She owns a production company, she said, and would herself be insulted by such questioning. The thing is, UCB isn’t like her production company. It isn’t like most other companies. The majority of its employees are not paid. The people in charge describe it as a collective, a family. One of them is a multimillionaire TV and film star whose brand rests in no small part on her liberal politics, though these politics contain a substantial carveout for the business she built on free labor. It's true the questions may be insulting; the UCB4 have no legal obligation to face them. Their obligation is moral. They can afford to weather the insult.

Talk to almost any UCB worker about UCB and they'll eventually point to the theatre’s central irony, how it’s become what it originally opposed: the Man, the system, the status quo. The irony of the irony is how quickly this actually happened. It took only a decade for the punk rock alt-comedy theatre to become its owners' personal bank.

Cover image via Marco Verch/Flickr, licensed under Creative Commons.