The Fire Cycle

we interrupt our normal programming

If you can swing it, a mere six bucks a month will help keep this newsletter going. Thanks!

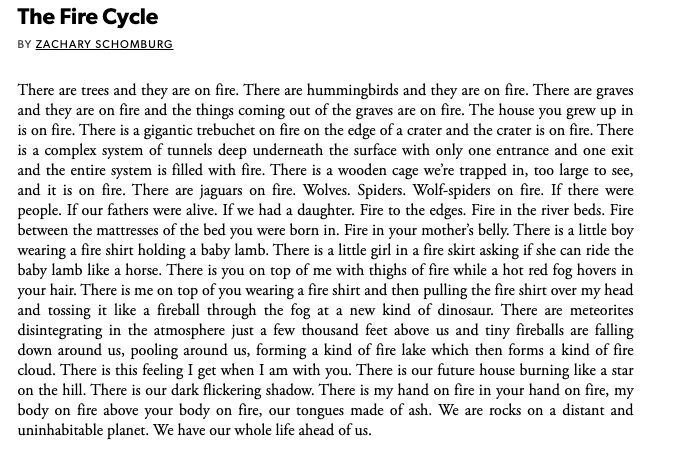

All week Idaho skies have been grey with California smoke and I have been thinking of this poem by Zachary Schomburg:

I have a soft spot for storybook-type poems like this, which use repetitive, whimsical language to tease out surprising emotional resonance from their subjects. It follows the same format as many humor pieces (and improv and sketch comedy, for that matter), first broadly sketching out a world and its rules, then deepening and transforming them before they become too familiar to the reader. I think of it like an orbiting telescope pointed deep into outer space. Close, bright objects register quickly, like simple declarative sentences that tell you where you are and what’s happening. As the telescope gathers light from distant reaches, unseen celestial bodies slowly become visible, even sharp, and our recognizable cosmic foreground gives way to a universe of dazzling new structures. (In “The Fire Cycle”’s case, a list of burning things comes to reveal an intense, doomed-yet-just-beginning relationship between speaker and reader.) It turns out that the longer you stare into the void, the more clearly you see that it’s not a void at all.

One way to think of poetry is as a force generated by the tension between order and chaos. You could also call these silence and noise, white space and text, unconsciousness and consciousness—choose your own duality. The sayable ventures boldly forth into the unsayable, which presses it right on back: voila, a poem. Chaos, order. The fun part is that each side of the duality is both. The void was perfectly orderly until it came to be filled with stuff; or, it was perfectly chaotic until stuff came along to give it order. A poem is perfectly silent until someone goes and puts words into it; or, it’s every noise combined until someone goes and puts silence in exactly the right places. Poetry is the creation of order within chaos and chaos within order, each fashioned into a new form of the other. This doesn’t really make sense, but only in the way dreams don’t make sense when you wake up from them. Until that point they make all the sense in the world.

What I love about Schomburg’s work is how viscerally it evokes that dream-feeling where nonsense is indistinguishable from sense. “The Fire Cycle,” like many of his poems, is small and orderly—a compact block of text—yet full of chaotic imagination. James Tate is another poet known for this effect. Here’s his poem “Debbie and the Lumberjack,” from his posthumous last collection The Government Lake:

I’m sorry I never said goodbye. I’m sorry I forgot your

birthday. I’m sorry I ever met you. I’m sorry I bought you

that drink and made you sick. I’m sorry I couldn’t find the way

to the hospital. I’m sorry I couldn’t remember what kind of roses

you liked. I’m sorry we fought over such a small thing. I’m sorry

I let the lion get too close to you. I’m sorry I taught you English

all wrong. I’m sorry we flew backwards in a storm. I’m sorry

you never got to eat a meal with my friends. I’m sorry you fell

off that elephant. I’m sorry you never learned to fly. And so many

more things I can’t remember or choose not to remember. It’s just

that I’m having trouble with the details. Was it you who swatted

me like a fly when I tried to touch you one Friday night? Was that

you who climbed in my window and slept beside me without a word?

Was it you who made the house fall down by simply breathing on it?

We left one day and never came back. We disappeared in the forest

and were never seen again. Someone dragged us out of the bog.

They cleaned us up and made us new again. We walked down the

street as if we had always lived there. We went to parties and

no one knew a thing. We woke up one morning and had our lives

back. I got a job and things went swimmingly. You acted as if it

had always been like this. Then a dinosaur came into our lives.

We fed it and took good care of it. But it wrecked the house

and we had no place to live. We dragged it around for a while.

It ate so much we had to move to the forest. We had no friends and

I lost my job. We thought of trying to kill the monster. Then

one day it wandered off. I accused Debbie of not caring for it

enough. She accused me of the same. We moped around for a while,

not knowing what to do. A hunter discovered us and brought us back

to civilization. I set up a little shop on 14th Street. But

Debbie wasn’t happy there. She ran off with a lumberjack and

hasn’t been heard of since. I only hope the dinosaur is one

step ahead of them. Or not.

Like the Schomburg poem, this one moves from image to image at an emotionless clip that belies each image’s emotional weight. They vanish as quickly as they appear, like the memories they represent. Tate uses short sentences with parallel structures to build a sense of momentum (narrative and emotional) that he occasionally interrupts with new sentence structures. The content is chaotic, the form more or less orderly. Like a good joke, the poem creates and subverts the reader’s expectations, giving you a rough sense of what’s going to happen just so it can give you something a few inches to the left. (A lion, a question, a bog, a dinosaur, an affair with a lumberjack.) Also like a good joke, it’s pretty funny. And rather sad. How can something so small and so light contain so much pain? That’s poetry for you.

This brings us to one other quality these poems share with all good poems, which is that they feel true. Authenticity in art is near impossible to quantify, so I won’t spend much time on it here, other than to say this. In “The Fire Cycle,” the poem’s form allows you to feel first its speaker’s awe at the world burning down around him, then his acceptance and even embrace of this loss, which he inexplicably ties to renewal. And there can be no doubt that the speaker in “Debbie and the Lumberjack” is at the end of his life, surrounded by ghosts of all the hurt he caused, all the joys that inevitably hardened into sorrow. Each poem yields at its end to a world beyond the speaker’s understanding or control; its formal energy turns out to be that world’s energy, which we can now recognize as the force moving through us too. The job of the poem was to tap into it.

I am writing about poetry in this edition of my comedy newsletter in part due to the age-old excuse of “the nation’s overlapping horrors were particularly distracting this week, causing me to fall behind on a couple other essays, and also I have a dog now (who ate my homework).” But I have also been pondering these poems all week, and through them the broader role of art in helping us experience that otherworldly energy. (Maybe it’s not quite otherworldly: as the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard said, “There is another world, and it is this one.”) When I think of all my favorite comedians, I realize that’s exactly what they do. Conner O’Malley, Jo Firestone, Joe Pera, Kate Berlant, Carmen Christopher, Reggie Watts, Aparna Nancherla, Maria Bamford, Sarah Squirm (this is an abbreviated list!)—they all make me feel transported to a realm they alone can access. Some do it by channeling that realm’s chaos; others, its peculiar sense of order. It’s a physical experience, whether because it sends me into fits of cry-laughter or because it soothes me, maybe even gives me chills. You might even call it spiritual.

Am I talking about art as escape? I don’t think I am. The effect is not to remove me from my own reality but to challenge and expand it; not to distract me from my own concerns but to make them smaller, more recognizable, less threatening. This is what I miss most about live comedy right now. It’s such a special thing, to walk into a small dark room and out into a bigger, stranger world. I can’t wait to do it again.

One more poem before we call it. Steve Scafidi’s “Lines for the Gates of a Cemetery”:

We had bound volumes of Persian

geometry and guitars made of cedar.

We had loose talk and shivering

as snow fell from the Eiffel Tower.

We had dishes and the bloody dream

of a flea sleeping in an eyebrow.

The sadness of being was it turns out

a kind of joy and everyone suffered

as they disappeared. We had rivers

flowing over top themselves and green

molecules and the slow eyes of sheep.

We had a use for things. We knew

the names of a thousand kinds of tea.

We had the white possum in the dark

with the other tiny possums holding on.

It's sad. We didn't know what we had.

And we had iodine in tiny blue jars.

We had eucalyptus trees and the planet

Mars circled with us through mizzen

dot-light of the distant stars. We had

the tintinnabulation of bells and a word

for everything. The pink dumb

moon rising and death with a top hat

quietly laughing at us as he passed.

Even that we will miss. Even that we loved.